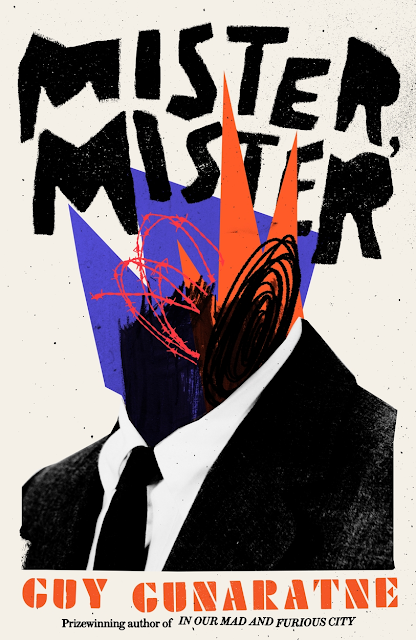

Book Review - Mister, Mister

Guy Gunaratne’s 2018 debut In Our Mad and Furious City announced a bold new voice, won several literary awards and was longlisted for the Booker Prize. Their sophomore, Mister, Mister, also partly set in London, is equally compelling. Gunaratne, who has a background in human rights journalism, says they were inspired by the story of Shamima Begum (the radicalised British schoolgirl who joined Islamic State in Syria, and was stripped of citizenship in 2019). The novel explores Britishness — who gets to belong, who doesn’t — and how resentment proliferates among those who remain outsiders.

Set between 1990 and 2015, and written as an episodic picaresque (after Charles Dickens), we follow the “life and times” of Yahya Bas, son of an Iraqi father and an English mother. Yahya is treated like an outcast from birth. He lives in a communal home in East Ham with several women (deserted wives, survivors of domestic abuse) who he refers to as “Other Mothers”. They call him “goat-boy”. His real mother, Estella, a former primary school teacher resides on the top floor of the dilapidated building, medicated, sewing and muttering to herself. His father Marwan, an oud player, returned to Iraq soon after his birth. Yahya’s uncle, Sisi Gamal, a “soapbox muezzin”, takes him in hand and introduces him to Islamic poetry.

When Yahya finds a stash of his father’s western books, he devours them on the buses he rides while skiving off school. This early love of words helps transform him into a radical poet. After photographs of torture emerge from Abu Ghraib prison (where the US held political prisoners during the Iraq war), he joins various online forums as Al-Bayn (a near homonym of Albion; bayn is Arabic for “in between”). His incendiary verse gets him noticed by other marginalised youth as well as by British intelligence.

We swiftly realise Yahya is an unreliable narrator, who relishes the opportunity to adopt multiple identities and assemble “a new and louder life”. Yahya becomes Zeinab, and travels to war-torn Syria on a false passport in an attempt to find his father. Instead, he ends up in the Free City, a fictional city between Iraq, Syria and Turkey, a community of the displaced fleeing violence. When the US coalition leaves the region, the city is dismantled and its inhabitants become refugees. But Yahya’s past as a jihadi poet haunts him on his return to England and he is detained indefinitely in the Bleaker House Immigration Removal Centre (another nod to Dickens) on the outskirts of London.

Yahya relates his story to Mister, the anonymous officer who interrogates him. Yahya has cut out his tongue so he can write his testimony and avoid dialogue with his interrogator. This allows him to reinvent himself once more, rejecting the various guises he has adopted throughout his life. As Gunaratne has said of Yahya: “Even when forced to define himself, he isn’t searching so much for belonging rather questioning the concept of belonging itself,” While Yahya believes he has “won” by asserting his right “to tell my own story”, and reclaim the narrative, we realise he has merely returned to the ranks of the disenfranchised.

Through this layered approach, and a keen ear for language, Gunaratne builds Yahya’s skewed perspective to terrific effect. Their memorable anti-hero raises interesting questions about identity in Britain today and the novel is a powerful account of a life unravelling.

Originally published by the Financial Times