Book Preview - The Young Pretender

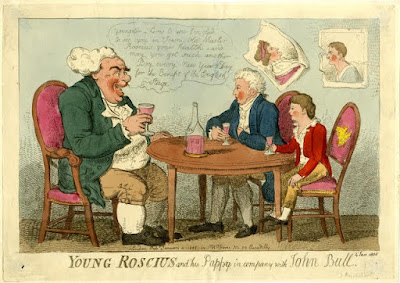

William Betty, nicknamed Master Betty, was a popular child actor of the early nineteenth century whose celebrity status was exploited by his father. He became known as “the Young Roscius” and as a young teenager was celebrated by theatre lovers up and down the country.

Michael Arditti’s twelfth novel, The Young Pretender, explores the Master Betty phenomenon. Arditti was inspired by an exhibition about the Georgian Playhouse at the Hayward Gallery. He tells me: “there was a small section, Bettymania, about the extraordinary boy actor who dominated both the London stage and London society for two years from 1804 to 1806. Like many people then and now, I’d never heard of him (though of course I hope that will change!) even though Kemble and Mrs Siddons (the Ian McKellen and Judi Dench of the age) retired for eighteen months rather than compete with him.”

The novel is written as a memoir, narrated by twenty-year-old William, who is planning his stage comeback. His past, and the reasons for his demise, remain something of a blank until he starts reconnecting with the fellow actors, managers and prompters he worked with in the past. “I am Mister Betty now,” he has to constantly remind them.

We learn that Betty’s recently deceased father, whose drinking, “gallantries” and gaming were well known, exploited his son’s youth, naivety and beauty for his own ends. Master Betty was celebrated for his energetic portrayals of Osman in Voltaire’s Zair, Young Norval in John Home’s Douglas, Selim in John Brown’s Barbarossa and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. As he recalls: “The Prince of Wales received me at Carlton House and presented me with a coach and four. The greatest lords and statesmen of the day attended my performances and invited me to fetes and banquets. Painters painted me and poets eulogised me. Duchesses vied to drive with me in the Park. All this before I had attained my fourteenth birthday.”

Tutored by the prompter Mr Hough, it was Betty’s youth, his talent for flawless recitation, that seemed to fascinate, rather than his rudimentary understanding of Shakespeare and stage craft. When Betty’s voice broke, “his cheeks filled out and his upper lip bristled, amid other palpable signs of manhood”, his popularity waned. “The Young Roscius took his final bow at an age when the common run of players had yet to take their first.”

Arditti’s account reminds us how quickly careers can be made and broken. He says: “Master Betty’s story speaks powerfully to us today about both the treatment of children and the nature of celebrity. Betty was, arguably, the first modern celebrity. He was mobbed whenever he stepped into the street; people died in stampedes to see him. As a novelist, I’m particularly interested in the effect of such early adulation on a person’s psyche, which is why I’ve set the story during his comeback at the grand old age of twenty!”

At the height of his celebrity, Master Betty was paid the unprecedented salary of 75 guineas a night at Drury Lane Theatre in Covent Garden. As an adult, we discover, Mister Betty is overweight and a reprise of his previous roles may be foolhardy: “A clergyman, with clumps of white hair like a cauliflower, supposing that his cloth grants him licence, pokes me in the stomach and asks if I plan to play Falstaff.”

Arditti is best known for his twelve acclaimed novels but, in his early career, he wrote for the stage and radio and later reviewed theatre for a host of publications. He also had a short directing career – at university and then for a year on the London fringe. He had several plays performed on the stage and on radio, but claims, “thankfully, I realised that such talents as I had were better suited to the more discursive form of fiction.” Nevertheless, Arditti’s interest in theatre and long career as a critic clearly coloured his novel and his descriptions of the stage business are particularly fun: Group rehearsals were perfunctory, and the cast spent little time together. When they did meet, they were often under-voiced and under-powered leading to surprises on opening night.

Why was Master Betty popular at this particular time? Arditti claims several factors. “After his fall from grace, former admirers such as Byron lined up to deprecate him, but he must have been hugely gifted, in order to hold his own against adult actors and in vast theatres like Drury Lane and Covent Garden. It’s telling that the great Victorian actor, Macready, who knew him as a boy, championed him in his memoirs. He also had huge novelty value at a time when the nation was desperate for relief from the Napoleonic wars. And of course he was very beautiful, which, as The Young Pretender shows, was a mixed blessing.”

It’s an impeccably researched novel and a compelling read about the fickle nature of fashion. Arditti transports us to another time and reminds us that the perils of early fame and fortune are nothing new.

A shorter extract of this feature was published in the Camden New Journal