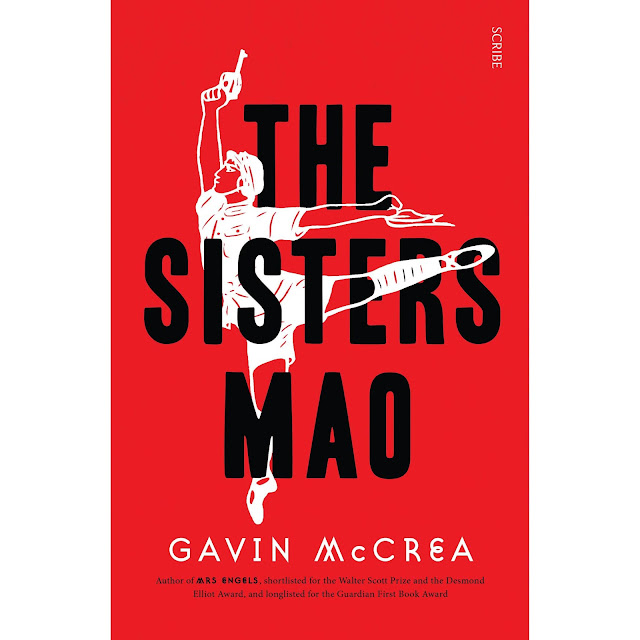

Book Review - The Sisters Mao

Narrated by three women, and set against the backdrop of China’s Cultural Revolution and Europe’s sexual rebellion, The Sisters Mao almost feels like two books. One set of Gavin McCrea’s characters is shaped by personal concerns, the other, predominantly, by societal forces.

In London, in 1968, sisters Iris and Eva are members of a radical performance collective who squat in a large King's Cross building owned by their mother, Alissa, a celebrity actress. After Eva returns from the French protests of May 1968, the group plan an audacious attack on the West End theatre where Alissa is playing the title role in August Strindberg’s Miss Julie.

Through a series of flashbacks, McCrea illuminates the family’s past. Iris and Eva’s parents had been staunch members of the Communist party until Stalin’s purges saw them embrace Maoism. Eventually, they abandon revolutionary politics altogether. Alissa forges a successful theatre career for herself, while Paul closets himself away with a performance artist who outdoes them all. Their daughters are left to their own devices.

McCrea’s debut novel, Mrs Engels, introduced us to Lizzie Burns, an illiterate Irish woman and partner of Friedrich Engels. The Sisters Mao, second in a planned “Wives of the Revolution” trilogy, is similarly populated by real and fictional characters. McCrea has said he wants to “cumulatively tell the story of the 20th century through a fictional account of the development of communism”. (His third novel will begin in post-communist Russia and end with the 2008 financial crash.)

In this novel he takes us to 1974 Beijing, where Jiang Qing, Mao’s fourth wife, is rehearsing a gala performance of a model ballet, The Red Detachment of Women, in honour of Imelda Marcos’s state visit. She terrorises everyone involved. The meeting of the two wives is brilliantly realised by McCrea, who recognises that, despite their political differences, they are similarly ambitious and ruthless paramours. We see Jiang at the height of her influence — a crude, cruel despot — and at the end of her life: imprisoned, accused of “counter-revolutionary crimes”, writing letters to her late husband.

It took McCrea five years to complete The Sisters Mao. It is impeccably researched and he interweaves the personal and the political to great effect. But the novel is also uneven — by turns frustrating and inspiring — and could have been considerably shorter. Although some may consider his flawed, egotistical narrators nuanced, I found them irritating.

Iris

suffers from epilepsy, she sells LSD for a living and inexplicably drugs her

co-performers at a crucial moment. The detailed descriptions of acid trips are

tedious. Eva is deliberately pretentious, a martyr to the cause modelling

herself on “high-powered French intellectuals”.

The sisters, who resent their parents and each other, are deeply unsympathetic. Jiang is loathsome. Perhaps that is the point. McCrea is interested in exploring his characters’ ambivalence and astute on how political opinions evolve — his fictional creations mellow with age and the possibility of financial security, while in the case of his real-life subjects, power corrupts.

The novel made me recall a well-known photograph of Marcos and Jiang laughing together. By imagining what they shared in that encounter, McCrea humanises them.