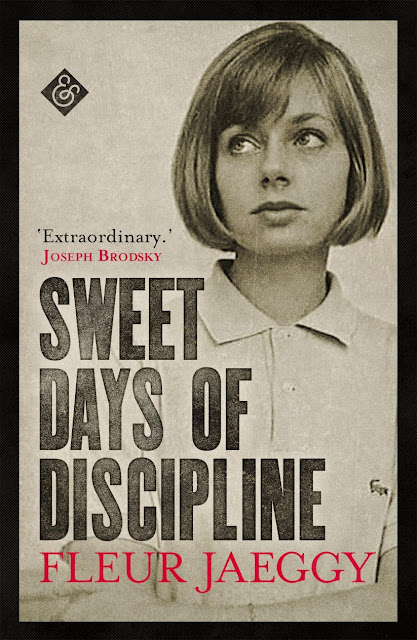

Book Review - Sweet Days of Discipline by Fleur Jaeggy

Death,

the abyss, the pain of solitude and the loss of loved ones are recurring themes

in Fleur Jaeggy’s fiction. Jaeggy grew up in Switzerland but lives in Italy and

writes in Italian. Her novella, Sweet

Days of Discipline, superbly translated by Tim Parks, is inspired by her

childhood in a Swiss boarding school in the 1950s and focuses on the torment of

adolescence. The original English edition (translated by Parks) was selected as

one of the Times Literary Supplement’s Notable Books of 1992.

Death,

the abyss, the pain of solitude and the loss of loved ones are recurring themes

in Fleur Jaeggy’s fiction. Jaeggy grew up in Switzerland but lives in Italy and

writes in Italian. Her novella, Sweet

Days of Discipline, superbly translated by Tim Parks, is inspired by her

childhood in a Swiss boarding school in the 1950s and focuses on the torment of

adolescence. The original English edition (translated by Parks) was selected as

one of the Times Literary Supplement’s Notable Books of 1992.

The

unnamed narrator has lived in boarding schools since she was eight, apart from

a brief period with a grandmother, who rejected her as “a savage”. She inhabits

a privileged, ordered environment where routine is paramount. And yet, we

quickly realise how unmoored she is from her family. Her mother resides in Brazil

and sends letters with instructions as to her schooling while her father lives

out of hotels and rarely visits. Consequently, the narrator’s moral parameters

are limited, she struggles with her identity, and has to rely on her teachers’ guidance

and affection, which are largely lacking.

Inevitably,

the girls develop crushes on one another and the narrator becomes fixated by self-contained

new comer, Frédérique: “Her looks were those of an idol, disdainful. Perhaps

that is why I wanted to conquer her. She had no humanity. She even seemed

repulsed by us all. The first thing I thought was: she had been further than I

had.” Very little happens as the days pass and the girls become women until Micheline,

a vivacious new boarder, arrives and the narrator swiftly shifts her

affections. Frédérique’s father dies and she has to abruptly leave school. Immediately

regretting her disloyalty, the narrator is convinced she will never hear from

Frédérique again. Looking back on the period she refers to as her “senile

girlhood”, she muses: “perhaps they were the best years… those years of

discipline. There was a kind of elation, faint but constant throughout… those

sweet days of discipline.”

A

few years later, the narrator stumbles on Frédérique living in destitution. Despite

signs of her friend’s fragility, the narrator sees her deprivation as “some

spiritual or aesthetic exercise. Only an aesthete can give up everything. I

wasn’t surprised so much by her poverty as by her grandeur.”

Originally published by the TLS